How does a waveguide circular polarizer achieve precise phase difference control from linearly polarized to circularly polarized waves through an asymmetric structure?

Publish Time: 2025-11-27

In the realm of microwaves and millimeter waves, the polarization state of electromagnetic waves is a crucial identifier. Among them, circularly polarized waves, with their unique spiral propagation, exhibit significant advantages in resisting polarization shifts, suppressing rain and fog interference, and receiving arbitrary linearly polarized waves. "Forging" simple linearly polarized waves into circularly polarized waves is a key skill in wireless system design. The waveguide circular polarizer is precisely such a highly skilled "forger." Its core secret does not stem from symmetrical harmony, but rather from the precise cutting and delay of the electromagnetic field phase within the waveguide through a carefully designed asymmetric structure.

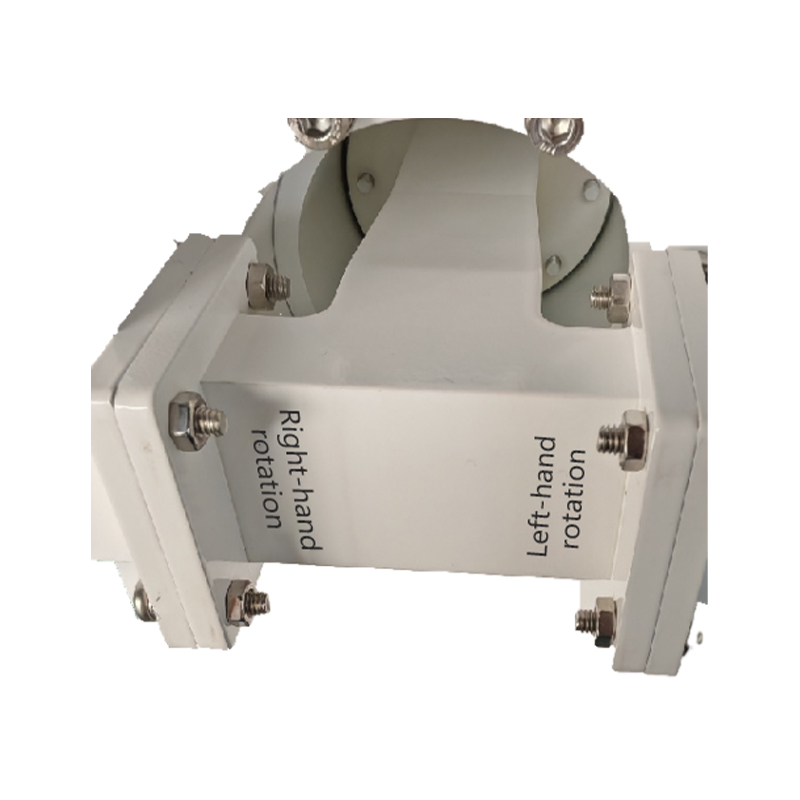

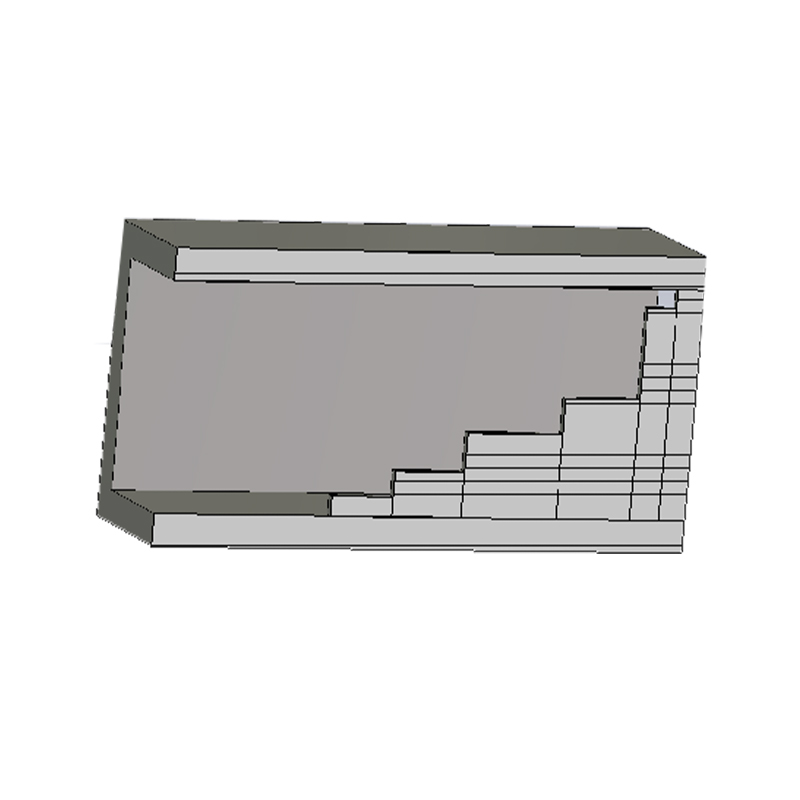

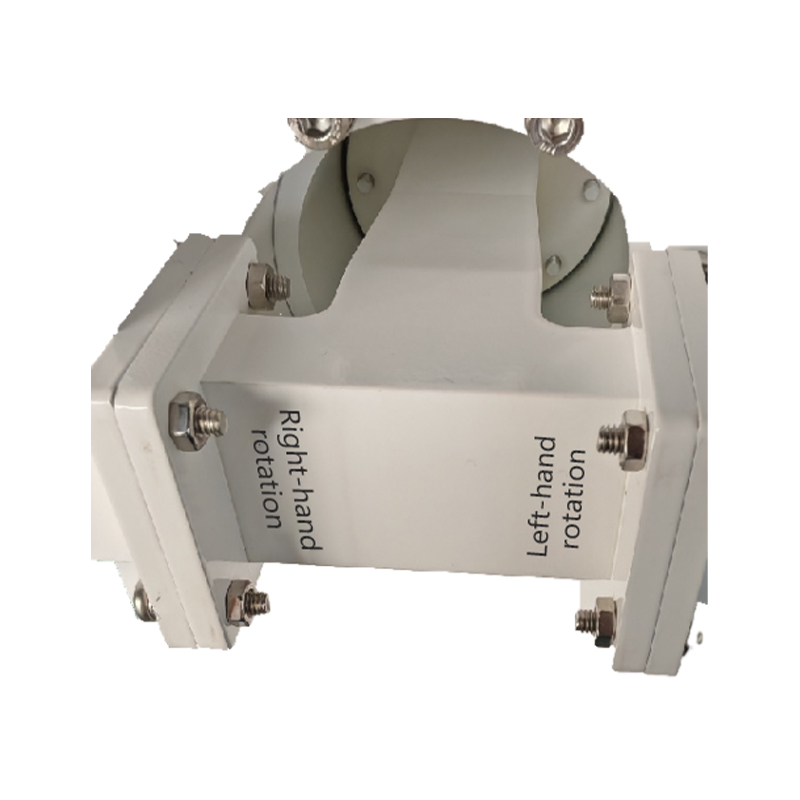

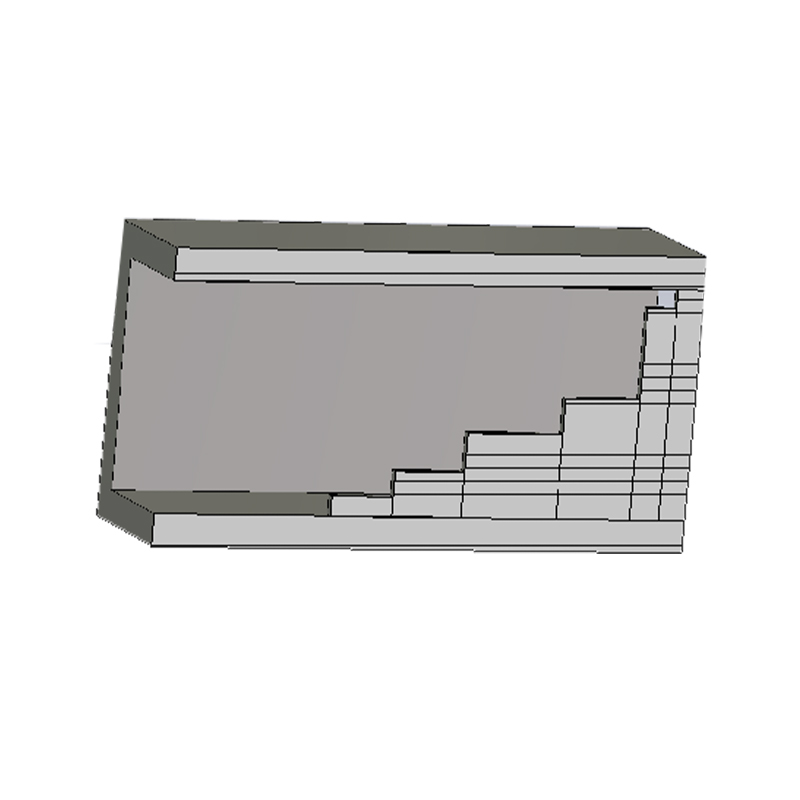

I. From Symmetry to Asymmetry: The Design Philosophy of Phase ControlTraditional waveguides have highly symmetrical internal structures. Whether rectangular or circular, their two orthogonal polarization modes are degenerate in propagation characteristics, meaning they possess the same phase constant. This means that a linearly polarized wave at 45° to the axis can be decomposed into two orthogonal components with equal amplitude and phase. These components propagate in parallel, failing to generate the 90-degree phase difference necessary for circular polarization.The design of the waveguide circular polarizer completely breaks this symmetry. Its core idea is to artificially introduce a controllable asymmetric structure within the waveguide, causing the two orthogonal electric field components to experience drastically different "journey experiences"—that is, different propagation constants. One component is accelerated, the other delayed; or one travels a longer path, the other a shorter one. When this phase difference is precisely accumulated and modulated to 90 degrees, the two components change from "moving in step" to "stepping back and forth," thus creating a waltz of electromagnetic waves.II. Three Implementation Paths and Phase Modulation Mechanisms of Asymmetric StructuresThis crucial asymmetry is mainly achieved through the following classic structural forms, each a sophisticated art of phase manipulation.1. Dielectric Sheet Phaser: The "Velocity Difference" Caused by Refractive IndexThis is the most intuitive example of asymmetric intervention. In a regular waveguide, one or more dielectric sheets of a specific shape and orientation are inserted axially. This dielectric material has a higher dielectric constant than air. When a linearly polarized wave is incident at a 45° angle, its electric field can be decomposed into two components: one parallel to the dielectric sheet and the other perpendicular to it.The key is that these two components interact with the dielectric sheet to different degrees. The parallel component is more confined within the dielectric region, and its effective propagation velocity is significantly reduced due to the high dielectric constant of the medium. The perpendicular component, on the other hand, is less affected by the medium, and its velocity reduction is less. This asymmetry in propagation velocity caused by the difference in refractive index results in a fixed phase difference accumulated between the two components after traversing the length of the dielectric sheet. By precisely designing the material, thickness, insertion depth, and length of the dielectric sheet, engineers can, like a tuner, precisely calibrate this "velocity difference" to a 90-degree phase delay, thereby outputting a pure circularly polarized wave.2. Pin and Screw Arrays: "Local Obstruction" of the Perturbation FieldIf the dielectric sheet creates a comprehensive "velocity discrimination," then an array of pins or screws acts as a series of precise "local roadblocks" within the waveguide. These metallic protrusions are asymmetrically and periodically arranged at specific locations along the wide side of the waveguide.When a linearly polarized wave enters at a 45° angle, its two orthogonal components interact with these metal pins to varying degrees. For example, the component parallel to the pin arrangement direction experiences a strong perturbation in its electric field, resulting in significant local reflections and phase delays, much like encountering speed bumps on a road. The component perpendicular to this direction, however, almost "ignores" the pins and passes smoothly. This asymmetry caused by local field perturbation causes one component to be continuously "slowed down" relative to the other. By optimizing the pin diameter, insertion depth, spacing, and arrangement pattern, the cumulative effect of this perturbation can be precisely controlled, ultimately achieving a perfect quarter-wavelength phase difference at the output port.3. Stepped and Finned Structures: Geometric Reshaping of Paths and ModesThis is a more macroscopic and structurally-oriented asymmetric design. By directly machining stepped protrusions or etching asymmetric finned grooves into the waveguide walls, we essentially redefine the propagation path and mode distribution of electromagnetic waves geometrically.These structures couple the original regular waveguide mode to a series of higher-order or hybrid modes with different propagation characteristics. Through ingenious three-dimensional structural design, we systematically ensure that one polarization component is primarily coupled to the mode with the larger propagation constant, while the other is coupled to the mode with the smaller propagation constant. This is equivalent to constructing two paths with a fixed "length difference" or "impedance difference" for the two components at the physical level. This phase difference, directly imparted by the geometry, is intrinsic and stable. Modern electromagnetic simulation software allows engineers to parametrically scan and optimize these complex structures, thereby "sculpting" the required 90-degree phase relationship with extremely high precision.

III. Precise Control: Engineering Refinement from Theory to PracticeHowever, simply introducing asymmetry is insufficient. Achieving "precise control" is the ultimate design goal, which requires rigorous engineering iteration and optimization.Bandwidth and Tolerance: A 90-degree phase difference at a single frequency point is relatively easy to achieve, but maintaining a good axial ratio across the entire required operating bandwidth of a polarizer requires frequency response design of the asymmetric structure. This typically means employing multi-stage, gradually varying perturbation structures (such as multi-stage steps or multiple rows of pins) to achieve wideband phase compensation.Impedance Matching: Any introduced asymmetric structure will alter the waveguide's original impedance, potentially causing reflections and increasing insertion loss. Therefore, impedance matching design must be performed simultaneously with the phase control structure design. For example, the dielectric sheet may be wedge-shaped, or the perturbation intensity of the pins may be designed to be gradually varied to ensure efficient energy transmission and avoid unnecessary reflections.Manufacturing Precision: In the millimeter-wave band, wavelengths are measured in millimeters, and the required phase accuracy corresponds to micrometer-level structural dimensional tolerances. At this point, the machining precision of the asymmetric structure directly determines the final performance. Choosing the right process—precision CNC machining, metal injection molding, or electrical discharge machining—becomes a crucial step in realizing the design blueprint.The waveguide circular polarizer is a prime example of the perfect combination of structural mechanics and electromagnetic field theory in microwave engineering. It reveals a profound truth: in the world of electromagnetic waves, the most perfect waltz is not born from absolute symmetry and balance, but from precisely calculated and designed asymmetry. It is through the meticulous craftsmanship of tangible elements such as the medium, metal, and geometric shape that engineers can precisely etch a 90-degree phase difference within the intangible electromagnetic waves, thereby mastering polarization and unlocking higher levels of wireless system performance. This is a precise art of control, silent within a metal cavity yet surging within a torrent of information.